Every professional pilot once undertook and passed their Recreational Pilot Licence (RPL) flight test. You’ve completed your theory and your flight training, and your instructor has told you that you are ready. But what should you prepare for in order to pass the test with flying colours?

On the day of the test, the CASA-approved testing officer will sit with you and run through how they will be grading you. It may seem daunting, but don’t stress, going for and passing your Recreational Pilot Licence flight test really isn’t as scary as you make it out to be. Plus, it’s all based on knowledge and skills that you have already demonstrated.

In-flight, your testing officer will want to see how you can demonstrate the following:

1. Steep turn through 360 degrees and back onto the original heading

The best way to do this is to make sure you give a thorough lookout to ensure you are in the clear before the turn. When you’re ready, hold the required amount of back pressure on the control stick so as to stay more or less the same altitude or level out in anticipation as you come back upon your original heading.

2. Stall recovery

For this part of the test, your testing officer will want you to demonstrate stall in various configurations. Make sure you remember the HASELL checks—Height, Airframe, Security, Engine, Location, Lookout—and know how to identify the symptoms before entering a stall.

Your instructor may also ask you to demonstrate how to recover a stall with a wing drop. If you make sure to use rudder rather than the ailerons, in the opposite direction of the dropped wing, you’ll be fine!

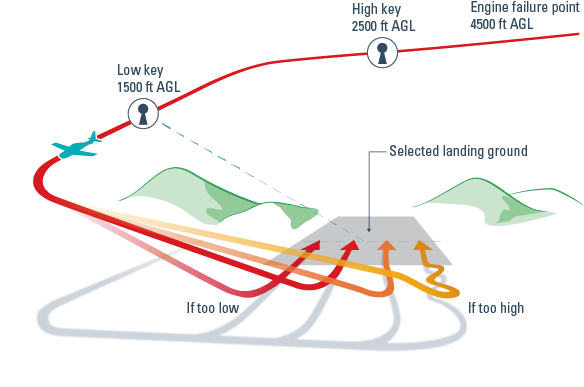

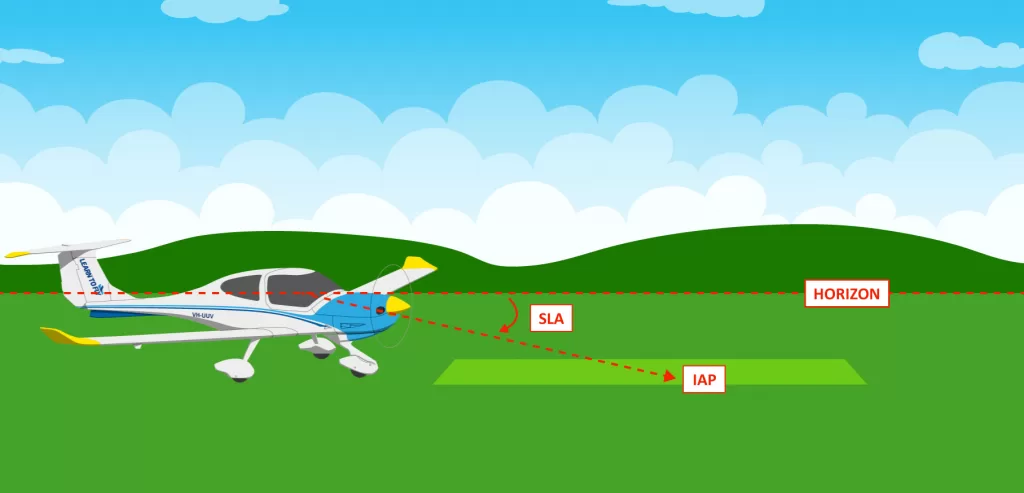

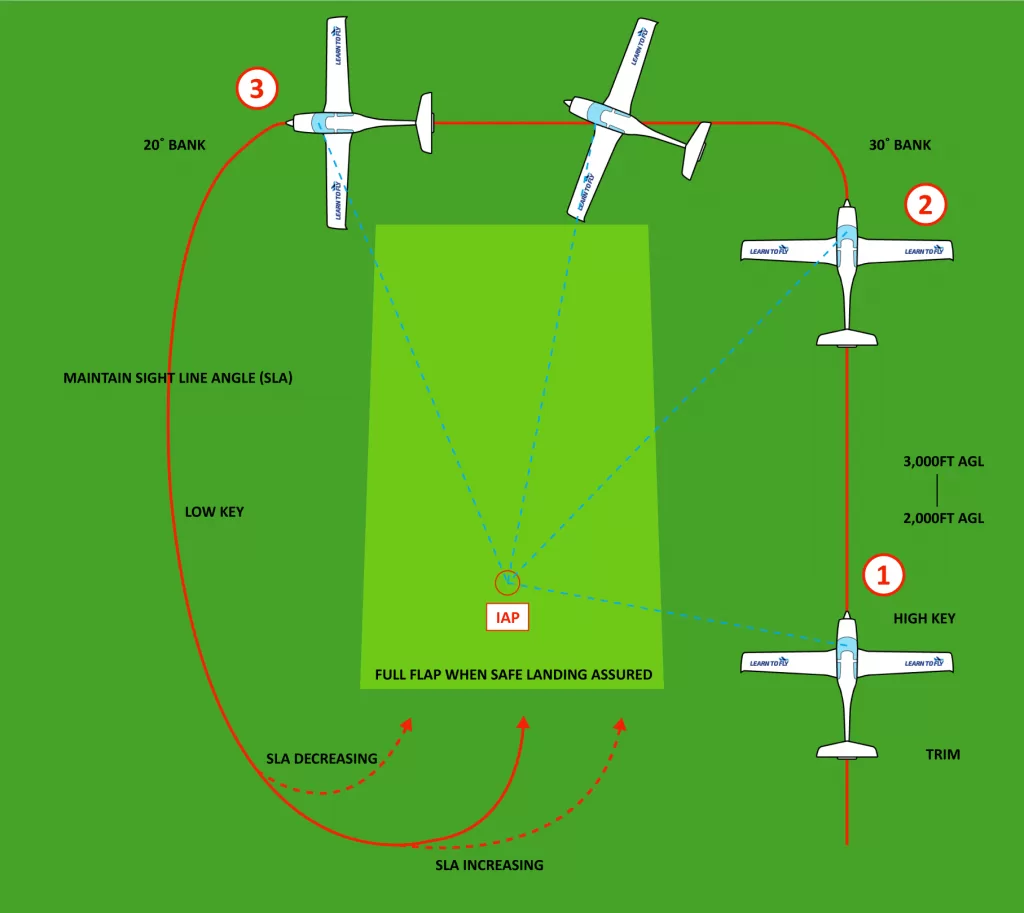

3. Forced landing

An integral part of flying – and your responsibility – is to be prepared for anything. To make a forced landing successfully, maintain control of the aircraft and select the suitable field. It is important to carry out all emergency checks. Conduct the passenger brief and mayday call, and always make sure to reassure the “passengers” that you are a trusted pilot and have been trained to handle emergency situations.

4. Instrument flying

The testing officer will want to see your demonstrated ability to fly on instruments alone under the hood. To do so, ensure you stay within the +/- 100 of the requested altitude and +/- 10 of the requested heading.

5. Circuit flying

The final part of passing your RPL flight test will have you demonstrate how to fly a squared circuit pattern and control your speed and altitude when doing so. Make sure you can also land the plane with different approach configurations, and manage engine failure after take-off and in the circuit.

Remember your inbound radio calls as you return to Moorabbin Airport’s control zone, and congratulations, you’ve completed the test.

After passing the RPL flight test and obtaining their RPL, students are qualified to fly within 25 nautical miles of the departure airport and carry passengers, during daylight in good weather (VFR) conditions.

Remember that every professional pilot was once a student, itching to achieve their next milestone. Bombarding their flight instructors with questions about how many flying hours it would take for them to reach their First Solo, Training Area Solo, RPL, PPL and finally, CPL.

However, we know that while flying itself is a great adrenaline rush, you shouldn’t be in a rush when learning and attempting your exams. If you mess up any part of the RPL flight test, remember that it won’t be the end of the world. You will always be able to have another go.

For more information on our RPL course, email [email protected]/en or go to https://drift.me/learntofly/meeting to book a meeting and school tour. You can also get more handy flying tips by clicking below and subscribing to our YouTube channel!