If you have researched flying, you have likely heard the terms Instrument Flight Rules and Visual Flight Rules before. Or possibly their abbreviations – IFR and VFR. Essentially, these are 2 different sets of “rules” that determine when you can fly. But what do they mean, and what are the differences?

What Are Visual Flight Rules (VFR)?

Visual Flight Rules (VFR) refers to flights that can occur in conditions that allow the pilot to fly using visual cues outside of the aircraft. The pilot must be able to maintain visual reference to the ground and be able to visually see and avoid obstructions, and other aircraft.

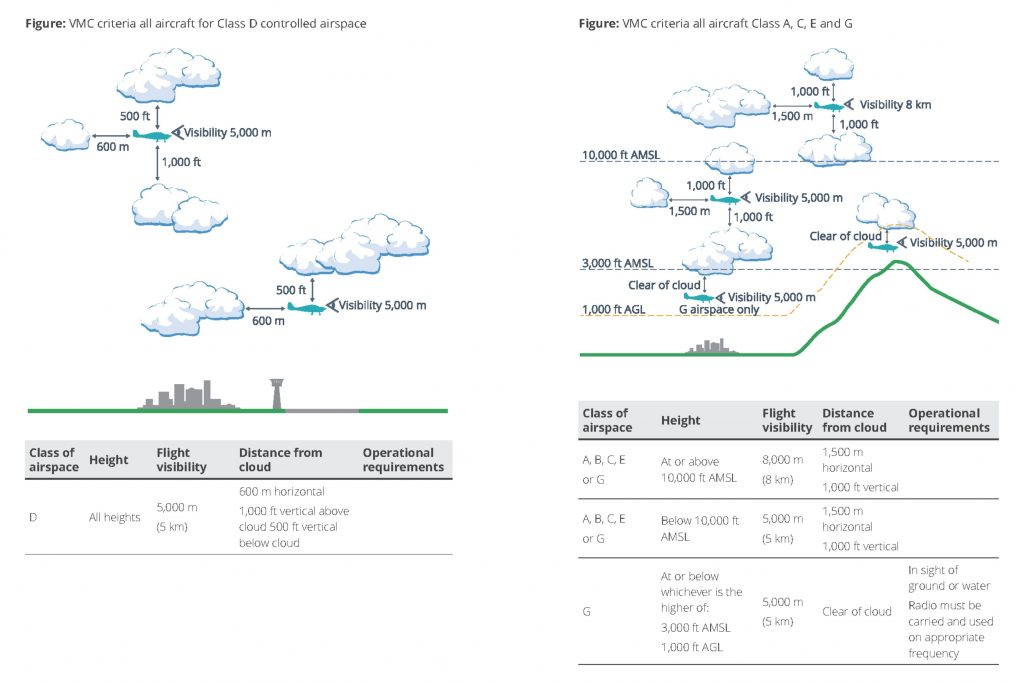

Such conditions are referred to as Visual Meteorological Conditions, or VMC. The required VMC are slightly different in different airspace classes. See the graphic below for more information, taken from CASA’s Visual Flight Rules Guide (VFRG). This is a great online resource that any pilot can download.

What Are Instrument Flight Rules (IFR)?

When VMC are not present and flights cannot be conducted under VFR, then they must be conducted under IFR. Instrument Flight Rules (IFR) are rules which allow properly equipped aircraft to be flown in non VFR-conditions, under what are known as Instrument Meteorological Conditions (IMC).

IMC are conditions where pilots cannot rely on visual cues, so they need to be able to fly using the aircraft’s instruments. This includes flying after dark, as well adverse weather conditions like heavy cloud and/or heavy rain. As a very broad and general rule, if it’s not VFR, it’s IFR.

Some exceptions can apply, such as Night VFR and Special VFR. Night VFR allows you to fly at night as long as other VMC are present. Special VFR can be requested when some but not all VMC exist for the proposed flight – this is usually used for training flights around an aerodrome and must be approved by ATC.

Flight Planning for VFR and IFR Conditions

As you might expect, flight planning is greatly affected by whether the flight will be conducted under VMC or IMC. Flying VFR affords the pilot far more freedom in planning. The pilot can choose the route and altitude of their flight – of course taking into account other airspace restrictions.

All IFR flights must be planned, with a pre-determined route that has been cleared by ATC. IFR flying involves set procedures for en-route, departure and approach. You will also obviously need an aircraft that meets IFR requirements.

When choosing whether to fly IFR or VFR, pilots generally consider the goals of the flight as well as the conditions. For a training flight that requires flexibility, VFR makes more sense. For longer or more direct flights, pilots may plan for an IFR flight even though conditions are potentially appropriate for VFR. This is due to the efficiency and added safety that IFR flight planning provides.

Flight Training for Instrument Flight Rules

As mentioned above, most training flights require a level of flexibility. That means that the majority of flight training needs to occur under VFR conditions. Whilst basic instrument flying forms part of initial flight training, it does not allow you to fly under IFR.

To be able to fly under Instrument Flight Rules, you need to obtain an Instrument Rating. Instrument Rating training teaches you how to fly using your instruments, without relying on visual cues outside the aircraft. To start instrument training, you must hold at least a Private Pilot Licence (PPL) or Commercial Pilot Licence (CPL).

Instrument Rating training includes en-route, departure and approach endorsements – which is what you will need to have when planning IFR flights. A lot of instrument training can be done in flight simulators, like our Alsim AL42 full cockpit synthetic trainer. This allows you to fine tune your procedures on the ground.

Our Private Instrument Flying Rating (PIFR) course is great for private pilots requiring IFR. It allows you to choose just the specific endorsements you require. For pilots who want to fly professionally, the Multi-Engine Command Instrument Rating (MECIR) is an essential choice as it includes both instrument and multi-engine training.

If you would like to find out more, you can email our flight training specialists at hello@learntofly.com.au. You can also visit https://drift.me/learntofly/meeting to book a meeting and a tour of our Moorabbin Airport training base.

Follow us on social media at https://linktr.ee/learntoflymelbourne